Why is Nobody Talking About NCAA Cap Smoothing?

Power conference programs that plan for revenue-sharing recalibration years could unlock a real strategic edge

College coaches, administrators, and newly minted general managers have been thrust into a new, professionalized era of college sports. In the wake of the House v. NCAA settlement approval, several NCAA regulations now mirror key features of professional leagues: revenue sharing, school-wide athlete compensation caps, roster limits, and multi-year contracts.

But unlike the NFL, NBA, or WNBA, there is no players’ union — and therefore no collective bargaining agreement to define the rules of engagement. Without that foundational document, many of the mechanisms that make pro roster-building predictable — minimum and maximum contracts, term limits, extension rights — are missing.

This leaves college decision-makers facing a fundamentally different puzzle. College basketball GMs and coaches shouldn’t hastily replicate an NBA-style “two-stars and depth” model because the economic assumptions don't hold. As a thought experiment: without a collectively bargained minimum salary, how much would a veteran 13th or 14th man in an NBA rotation earn? Almost certainly it would be less than the current league minimum.

These are the questions many inside college sports’ newly created front offices are thinking about. And while many frameworks from the professional sports world don’t cleanly apply, concepts from the NBA and NFL are quietly embedded in the House settlement, and programs of every revenue-sharing sport that navigate it strategically could gain a real competitive advantage.

Cap Smoothing.

Nobody seems to be talking about it, but they should be.

In the NBA, the salary cap is tied to Basketball Related Income (BRI), but growth is smoothed to ensure stability. Under the current collective bargaining agreement, the cap cannot increase by more than 10% year over year, even if league revenues surge. Excess revenue is effectively held back — either through the league’s escrow system or deferred cap adjustments — and spread across future seasons. This prevents disruptive spikes and allows teams to plan multi-year deals with far greater predictability.

Back in 2016, before formal cap smoothing was in place, the NBA saw a roughly 34% jump in the salary cap in a single offseason. That surge — driven by a new $24 billion media rights deal — led to some of the most infamous contracts in modern league history, producing windfalls for mid-tier free agents and financial headaches for general managers for years to come.1

While the House settlement doesn’t use the term explicitly, the structure embedded in the settlement functions to limit volatility in year-over-year team spending, allowing schools to project multi-year commitments and avoid unpredictable rev-share cycles predicated on fluctuations in nationwide college athletics revenue.

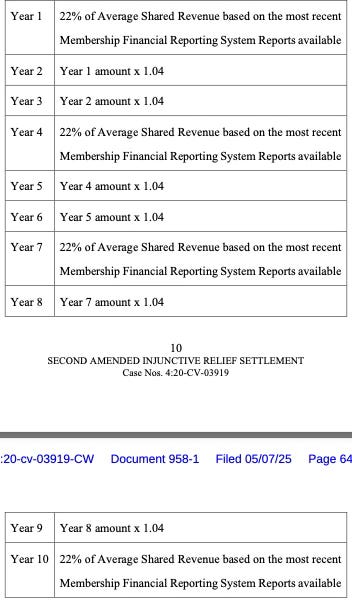

As shown below, rather than recalculating the athlete compensation pool annually, the settlement employs a three-year smoothing mechanism. In Year 1 of each cycle, a new baseline is set at 22% of “Average Shared Revenue” based on financial reports. For the next two years, that number grows at a fixed 4% rate — a built-in inflation escalator. The cycle then resets with recalculations in Years 4, 7, and 10 — these recalculation years should be examined and planned for very carefully.

For the first year of revenue sharing, schools will have the permissive ability to compensate athletes across all their sports teams up to $20.5 million. Schools looking to meet the cap will determine the budgets for each program based on institutional preferences and needs, with FBS football typically commanding 65-80% of the budget and men’s basketball hovering between 15-25%. At large, women’s basketball and baseball will make up the majority of the remaining funds.

While the $20.5 million figure is a hard cap on paper, the ability for schools to shift budget allocation year-to-year between teams allows athletic departments to tweak team-wide budgets to account for changing priorities or invest in a team that seems “one piece away.”

These three recalculations will be based on Membership Financial Reporting System (MFRS) reports, which aggregate revenue streams from institutions within the Pac-12, Big Ten, Big 12, SEC, and ACC, including football-independent Notre Dame.2

It is important to note that the House settlement grants Class Counsel the ability to accelerate two revenue-sharing recalculations during the 10-year term. If utilized, these player-led recalibration windows will initiate a new three-year smoothing cycle that deviates from the original schedule.3

These recalibrations will likely coincide with major media rights renegotiations — particularly in the Big Ten and SEC — and trigger earlier-than-expected increases to the cap. While this introduces a layer of unpredictability into long-term planning, front offices should operate under the assumption that the cap will continue to rise. The only question is when, not if.

Given the trajectory of media rights valuations and a heightened focus on revenue generation to offset the burden of athlete compensation, these recalibration years could yield significant spikes to schools' revenue-sharing caps.

Schools across the country have already begun adding talent fees to tickets and on-field sponsor placements to boost revenue. In the not-too-distant future, we could see jersey patches and conference naming rights sponsors, generating new revenue streams that dramatically enlarge the first revenue-sharing cap adjustment.

For programs that don’t foresee this dramatic change, they could be caught in a 2016 NBA situation where the value of players increases exponentially overnight. Unlike the NBA, collegiate programs aren’t required to meet a salary floor, which could mitigate the gross overpayment of athletes. Nevertheless, strategic management before these jumps in the cap can provide tremendous leverage to forward-thinking athletics departments.

While the NCAA does smooth the cap in non-recalculation years, the spikes in years 4, 7, and 10 could prove to be quite significant and require strategic management to navigate tactfully. The NFL, which I will delve into in more depth shortly, operates without cap-smoothing protections, and savvy GMs have utilized the backloading of proven impact players’ contracts as a strategy to positively leverage themselves in the short term without fully mortgaging their future spending power.

It is essential to note that these cap-smoothing and recalculation considerations apply only to power conference institutions that have the resources to meet the cap; smaller schools outside of the power conference will remain constrained by the resources they have available to compensate their athletes.

So, why is this an important consideration for college athletics decision makers?

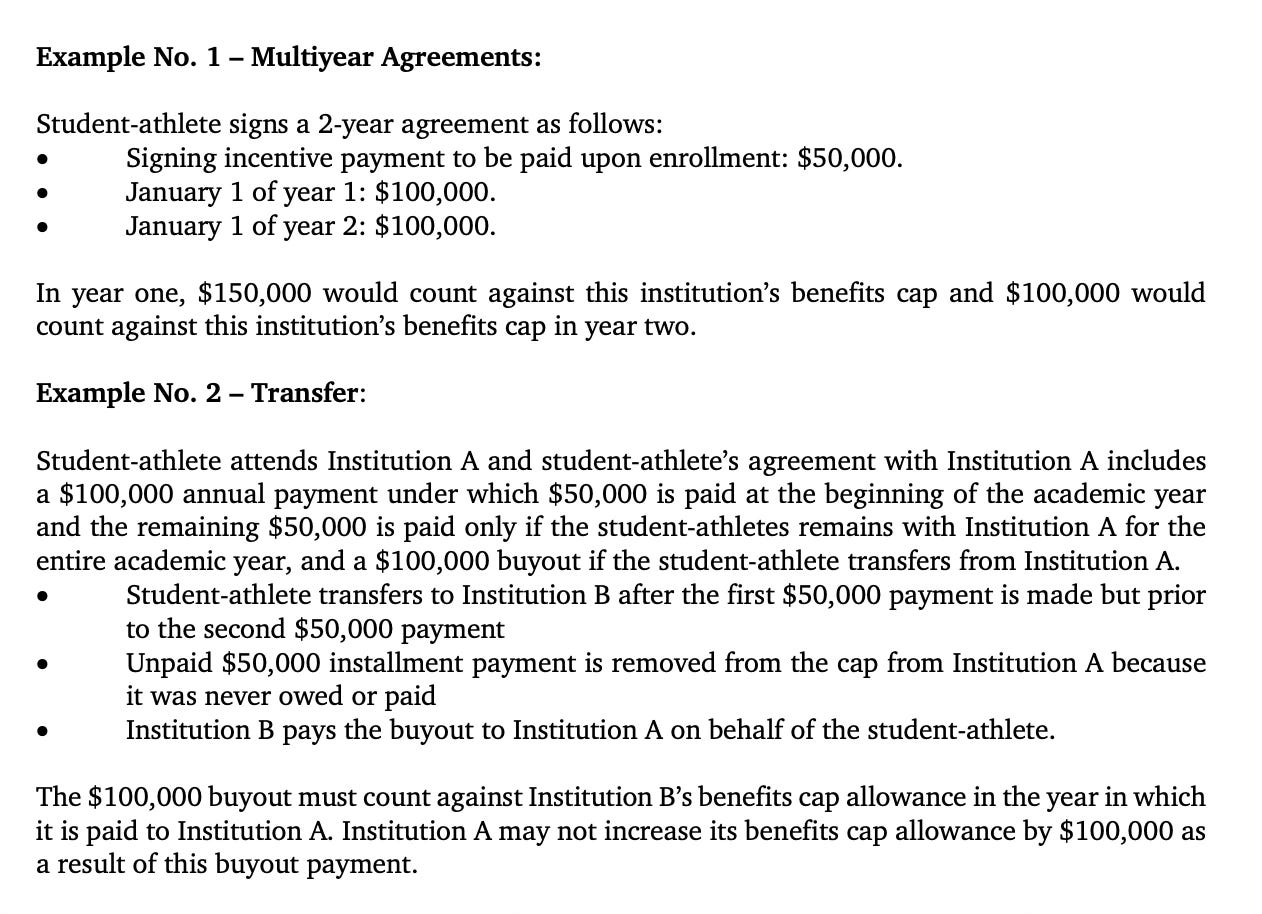

Recent NCAA guidance has provided rules for multi-year contracts:

Multi-year contracts provide institutions with the flexibility to get creative with payment schedules for athletes and allow teams to escalate payments year-to-year at any chosen interval, provided an athlete agrees to a deferred compensation structure. This can be utilized at initial recruitment or in the reconstruction or extension of an agreement early into an athlete’s eligibility.

Strategic management of cap spikes in recalculation years will likely be most exploitable in football, baseball, and women’s basketball, as athletes are precluded from entering their respective professional drafts until three years of college. In a top-heavy player compensation market, such as that of a blue-chip quarterback, teams can leverage heavy payments in recalculation years to provide an attractive compensation package that peaks after recalculation.

As mentioned earlier, the NFL doesn’t formally smooth its salary cap like the NBA. Teams often operate in long-term cap planning with the confidence that media rights revenues will continue to drive cap increases. Franchises routinely backload player contracts into future years — essentially betting that the cap will rise fast enough to absorb the impact.

Justin Herbert offers a solid example of deferred payment. After proving himself as a franchise quarterback, the Chargers signed him to a five-year, $262.5 million extension. The deal is structured to maintain roster flexibility early while pushing larger cap hits into later seasons — a common approach in the NFL seen with star QBs like Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson, Josh Allen, and Jalen Hurts.

In 2023, Herbert’s cap hit was just $8.46 million. His cap number jumps to $19.3 million in 2024, $37.3 million in 2025, and continues climbing through the life of the contract, eventually peaking at over $71 million in 2028. These escalating figures align with the expectation that increasing league revenue will lift the salary cap, softening the blow of backloaded contracts.

Of course, there are still structural differences between college sports and the pros that complicate this idea slightly. While not shown in the chart above, Herbert’s $16.1 million signing bonus was paid upfront but amortized over the lifespan of his contract. Under NCAA rules, an athlete couldn’t accept a signing bonus like Herbert’s without it impacting the cap in the year in which the payments were made.

Increasingly common NFL salary manipulation tactics, such as bonus proration and void years, don’t squarely fit into the NCAA model. Even so, the underlying logic of deferring cap-heavy years and backloading compensation in multi-year deals — especially when aligned with recalculation years — remains a viable, and potentially powerful, strategy for college athletic departments.

College programs now have a similar opportunity. While athletes aren't guaranteed contracts or collectively bargained protections, the combination of cyclical cap smoothing and multi-year deals gives schools the tools to structure compensation more strategically. For a breakout player who has proven themself in a first or second season, a backloaded extension — especially one that peaks in a recalibration year — could serve the same purpose: keep a star athlete in school while maintaining flexibility today and betting on a higher cap tomorrow.

While men’s basketball is not prevented from leveraging backloaded payments, it is unlikely that star athletes will be the ones inking these deals. With only one year of playing time required before NBA Draft eligibility, top prospects — often those commanding the largest cap hits — are less inclined to commit to backloaded, multi-year structures.

However, high-level contributors and role players without immediate NBA aspirations may find this structure attractive if it can net them more total compensation. These deals could be pivotal in freeing up budget space for one-year commitments to marquee talent.

Multi-year deals with backloaded compensation can be an extremely advantageous way to build championship windows, provide immediate roster flexibility, and exploit recalculation years.

In a system without a collective bargaining agreement, recalculation years and multi-year deal structures might become the closest thing to front-office leverage in college athletics. Cap smoothing isn’t something to gloss over in the House settlement — it’s a strategic tool to be exploited. Programs that understand how to use it will have an advantage in both the short and long term.

If you’re a coach, general manager, or athletic administrator thinking through how these changes apply to your roster, I’m always happy to connect to learn how you plan to tackle these novel challenges and share thoughts.

Some notable free agency signings in 2016: Timofey Mozgov – 4 years, $64 million (Lakers), Luol Deng – 4 years, $72 million (Lakers), Joakim Noah – 4 years, $72 million (Knicks), Ian Mahinmi – 4 years, $64 million (Wizards), Chandler Parsons – 4 years, $94 million (Grizzlies), Bismack Biyombo – 4 years, $72 million (Magic).

Per NCAA guidance “The MFRS revenue categories include ticket sales (does not include donations tied to season tickets), input revenue from participation in away games, media rights revenues, NCAA distributions and grants; non-media conference distributions; direct revenues from participation in football bowl games, as well as conference distributions of football bowl revenues; and athletics department revenues from sponsorships, royalties, licensing agreements and advertisements.”

Per the settlment: “Class Counsel shall have two (2) opportunities within the term of the Injunctive Relief Settlement to accelerate the re-calculation of the Pool based on the most recent Membership Financial Reporting System Reports available. If Class Counsel wishes to exercise their option, they must provide notice within thirty (30) days of receipt of the Membership Financial Reporting System Reports. A new three-year period shall commence in the first Academic Year after notice of exercise of the option, with the Pool amount increasing by four percent (4%) in the second and third years of such period.”

Noah Henderson is the Director of the Sport Management Program and a Clinical Instructor at Loyola University Chicago’s Quinlan School of Business. His work explores the intersection of law, economics, and the social consequences of college athletics, particularly in the areas of name, image, and likeness (NIL), athlete labor rights, and sports gambling.

Henderson helped amend Illinois’ NIL legislation and played a direct role in establishing early frameworks that facilitated the legal payment of college athletes at Student Athlete NIL. He continues to advise athletic departments, brands, and sports agents nationwide on NIL policy, legal compliance, and best practices.

He contributed extensively to Sports Illustrated’s NIL Daily, where his reporting and commentary helped shape public understanding of the evolving business of college athletics. His insights have been featured by ESPN, NPR, CNN, PBS, Sportico, the Chicago Tribune, and others.

Henderson holds a Juris Doctor from the University of Illinois College of Law and a degree in Economics from Saint Joseph’s University, where he was a four-year letter winner on the golf team.