What the NBA Can Teach College Basketball About Roster Continuity

In the highly transient world of college basketball, how important is roster retention? Data from the NBA shows clear advantages to keeping teams together.

On Friday, June 6, the House v. NCAA class action settlement received final approval, confirming a more professionalized landscape for revenue-college sports highlighted by direct athletic compensation. Starting this academic year, schools will transition away from third-party NIL payments for athletic performance and utilize their new ability to allocate $20,500,000 in institutional NIL revenue-sharing for athletic services.1

As the NCAA matures into its new quasi-professional model, the destabilization of previous NCAA athlete regulations is impacting not only the business of college sports but the game itself.

In recent years, the NCAA has lost the ability to enforce player transfer restrictions, and the concurrent emergence of a red-hot market for transferring athletes in both revenue and select non-revenue sports has made roster continuity across the college landscape highly volatile.

Over the past five seasons, overnight regulatory sea changes have continually presented novel challenges for coaching staff in recruiting and retention strategy — no sport illustrates this new reality better than men’s basketball.

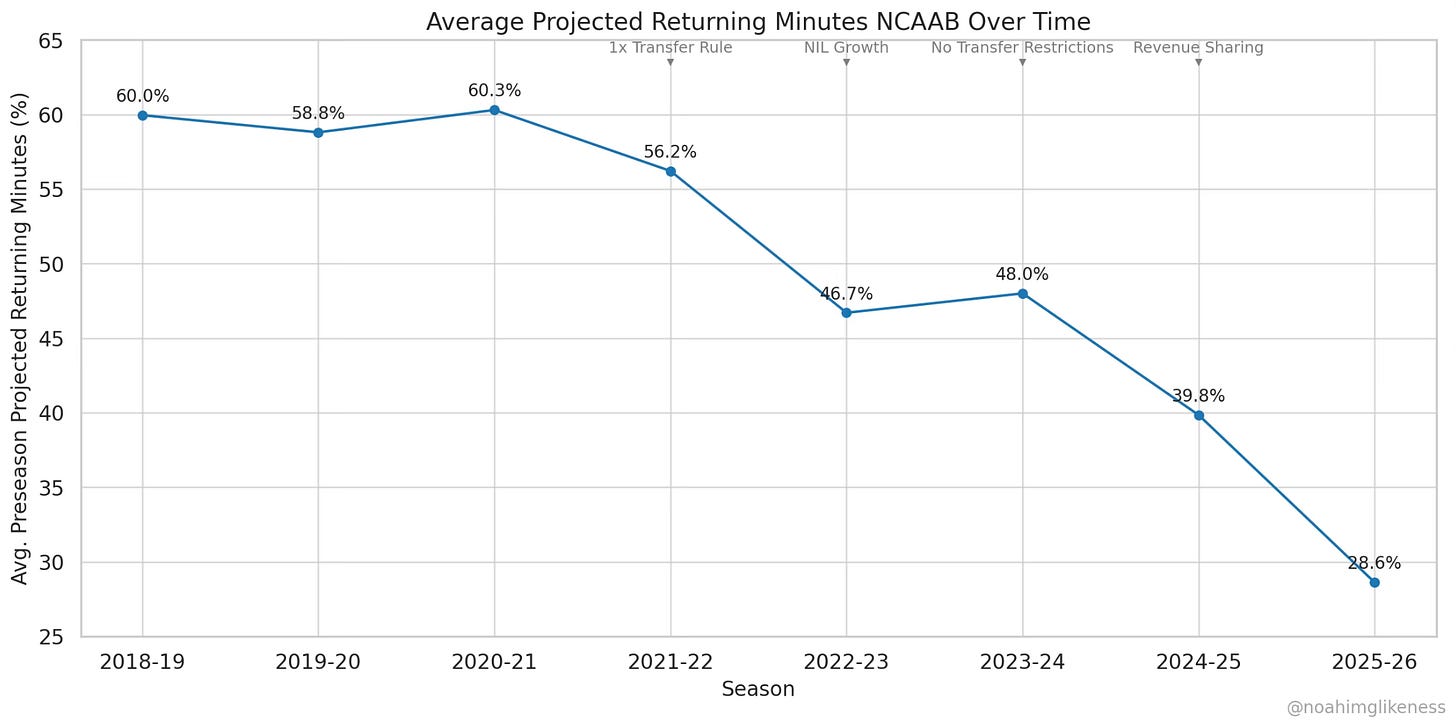

In the 2025–26 season, the average NCAA Division I men’s basketball team will return less than 30% of its total team minutes.2

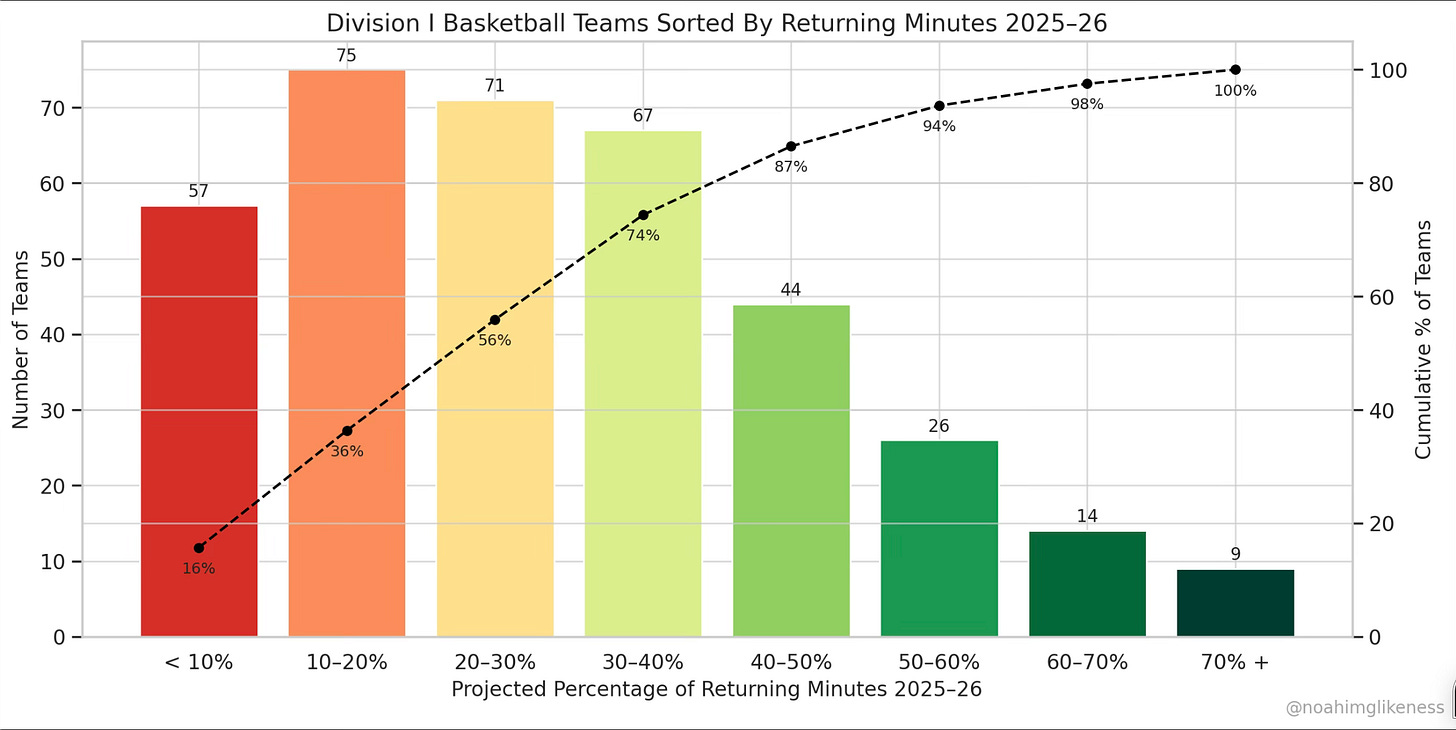

This year, 57 of the 363 total Division I programs are projected to have less than 10% of their total minutes returned. On average, Division I teams will return just 28.61% of their minutes, down from an average that hovered around 60% before sweeping changes to athlete compensation and player mobility began in 2021.3

The collapse in roster continuity can be traced back to four defining regulatory shifts. As shown in the data above, each structural change to NCAA enforcement power eroded roster continuity piece by piece.

April 2021: The NCAA adopted the one-time transfer rule, allowing athletes to switch schools once without sitting out a year. Previously, most transfers were required to redshirt unless granted a waiver.

July 2021: The NCAA formally recognized NIL compensation, allowing athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness. NIL collectives — donor-backed groups — quickly emerged as unofficial payroll arms, offering payouts to recruit and retain athletic talent.

December 2023: A federal judge granted a preliminary injunction in Battle v. NCAA, striking down the NCAA’s remaining restrictions on multi-time transfers. The NCAA codified the decision in April 2024, allowing athletes to transfer as often as they want, with no eligibility penalties.

October 2024: A federal judge granted preliminary approval of the House v. NCAA settlement, which created a quasi-salary cap for revenue-sharing payments for athletic departments, allowing schools to compensate athletes directly for the first time. The settlement also put in place salary-cap manipulation rules that limit the ability of third-party NIL collectives to provide athletic compensation.

With athletes’ newfound freedom of movement and substantial compensation on the table, the transfer portal has increasingly become the college basketball equivalent of the NBA’s unrestricted free agency. Players can test the market each offseason and transfer to the highest bidder.

Not every transfer is predicated on money alone – proximity to home, finding a program that offers more usage and minutes, leaving after being recruited over, amongst other considerations, incentivizes more athletes than only the impact starters who improved their market value to find new teams.

As shown by the data, player movement in the college basketball offseason has become the norm, altering many coaches’ recruiting priorities from development to a “win now” mentality. This has disincentivized high school recruiting, and now any school can emerge as a title contender overnight with a healthy budget and a single strong recruiting class from the transfer portal.

As college basketball professionalizes, schools have invested accordingly — hiring general managers, building front offices, and preparing for revenue-sharing. Beginning next season, athletes will be directly compensated through NIL revenue-sharing agreements, with basketball payrolls at top programs projected to reach $4–6 million annually.

As an investment, transfer athletes pose less risk than their high school counterparts. Proven success in any conference is an indicator that a player can compete at the Division I level while handling the social dynamics and temptations of being a college athlete.

With less risk, transfer athletes are compensated at a higher rate, and schools that can afford the price tags of proven athletes at the college level have often prioritized transfer players over high school recruits. For coaches of high-major programs, it seems prudent to have non-blue chip prospects be developed in someone else’s gym on someone else’s dime.

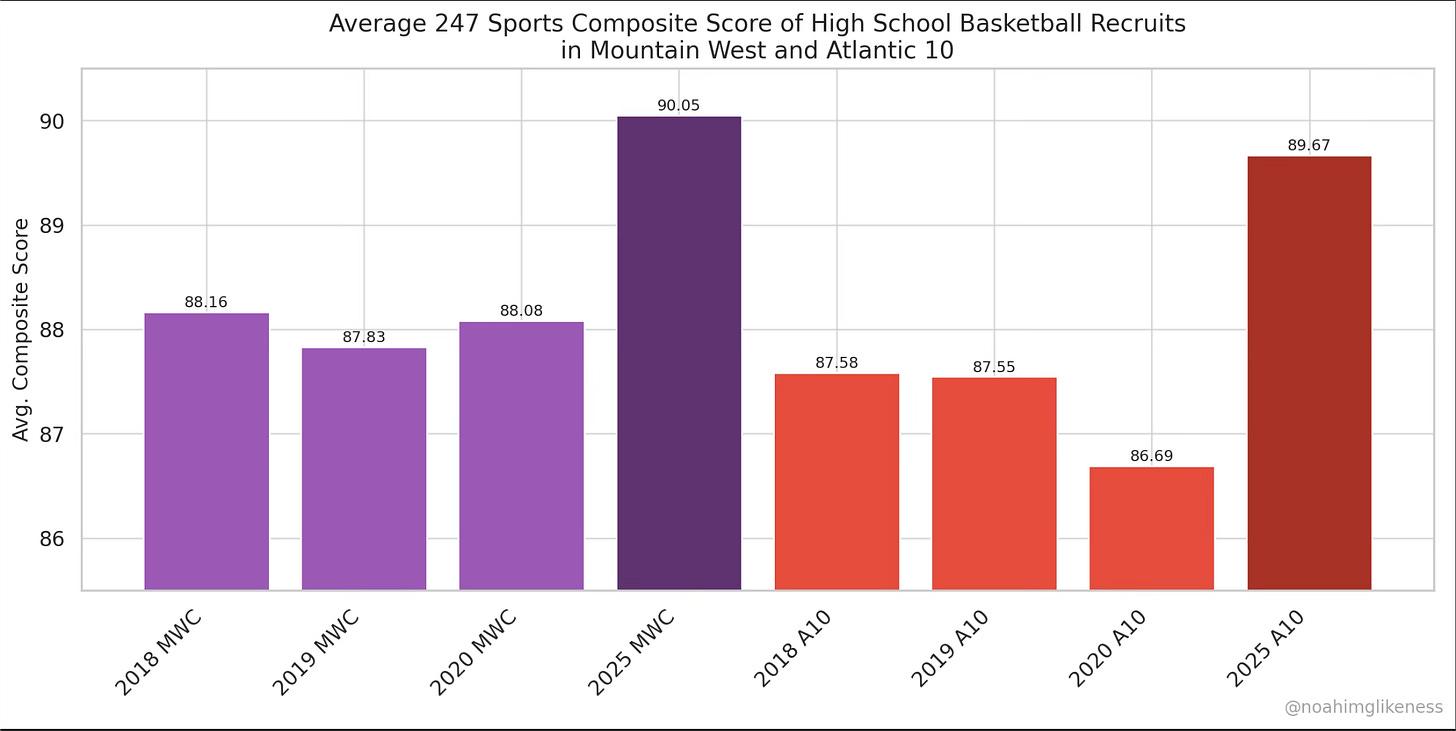

This has created a system in which mid-major conferences enjoy a significantly higher threshold of high school recruiting potential. The Atlantic 10 Conference and Mountain West Conference have seen substantial shifts in the caliber of prep recruits, with their average recruits jumping over 50 spots in national rankings. My full breakdown of this phenomenon can be found here.

This is a double-edged sword for mid and low-major athletic departments. For recruits at smaller schools that pan out, high-major programs with more NIL revenue-sharing dollars to offer can make offers that players’ original schools can’t match. This significantly increases transience and often strips smaller schools of players contributing significant minutes and usage year after year.

The cruel irony of college basketball recruiting for smaller schools is that the better you scout, the more turbulent your rebuilding process will likely look the following year.

However, the most recent phase of professionalization could stabilize the sport and restore some level of roster continuity, especially at the mid-major level. Rather than one-year NIL deals, schools are beginning to negotiate multi-year revenue-sharing contracts with athletes and their agents, including escalating payments (often paired with team options) and buyout terms, which disincentivize mid-contract transfers.

Still, as for the immediate future, only 23 of 363 Division I programs are projected to return more than 60% of their minutes in the upcoming season.

Nine of those 23 institutions are Ivy League, Patriot League, or military academy programs — uniquely insulated from the volatility sweeping the rest of college basketball. For everyone else, roster churn is the new normal.

High player turnover was once reserved for a select few coaches of blue-blood institutions who routinely lost talent to the NBA draft through the early-entrant process; now, most schools must approach roster construction like that of Kentucky and John Calipari, who did so throughout the 2010s with great success.

Very few schools are blue-bloods capable of replicating this system. Historical data from college basketball rankings sources KenPom and BartTorvik support the notion that continuity yields positive returns. Intuitively, teams that operate similarly to their previous year’s system yield an advantage; however, the data is noisy, and the tangible impacts are challenging to quantify.

Ultimately, prioritizing monetary investment in roster continuity becomes tough to justify when teams operate on a fixed budget with many competing variables that also impact success.

For those looking to optimize their long-term strategy, this presents a challenge – very little can be learned from historical college basketball data. Due to the structure of the old NCAA rules, player movement was heavily restricted, resulting in limited data on teams that had been previously impacted by radical roster reconstruction.

More importantly, the caliber of players that can be acquired through the transfer portal is significantly different from what it was before the emergence of today’s unlimited transfer system.

In the pre-professionalized college basketball world, teams often replaced minutes through a developing bench player, a freshman recruit, or the acquisition of a rare graduate transfer. In regards to athletic talent, radically different players are filling the gaps in minutes at all levels of college basketball, and that makes all old data somewhat meaningless.

Consider a Big Ten program replacing a departing starter. In the past, that role might have been filled by a freshman or a third-year bench player who has developed into a contributor. Today, that same program can land an All-MAC first-team athlete with 1,500 college minutes under his belt. The method of replacement has changed; programs can now acquire talent and dependability from replacements.

In short, the current transfer portal is deeper and more talented than it has ever been. It’s a different landscape in its entirety, and much of the old continuity logic no longer applies.

Even with this intuition, looking anecdotally at the Final Four teams from the 2024-25 season, we can see that Auburn, Florida, and Houston benefited from substantial contributions from players who had been in each respective system for multiple years. While many of the players did not start their collegiate careers at their respective schools, they were not in their first season with the program or thrust into radically different roles year to year.

The one obvious counterpoint is Duke, whose predominant usage came from an exceptional freshman class that includes three players projected to be selected in the top ten of the upcoming NBA draft, as well as a third-year anchor, Tyrese Proctor. Talent, or more specifically, immense talent, can still yield success without continuity.

Ultimately, Duke fell down the stretch of their Final Four game to Houston’s experienced core of L.J. Cryer, Emanuel Sharp, and J’wan Roberts, all of whom played starter minutes in head coach Kelvin Sampson’s system the year before.

If college basketball is closer and closer to behaving like a professional league, what does retention look like in a league where player movement is regulated like the NBA?

Interestingly, roster continuity in the NBA has historically hovered around 66%, not far from the rate NCAA teams used to retain before the introduction of NIL and free transfer rules. From 2000 to 2024, the average NBA team kept roughly 66% of their minutes year to year, only a 6% difference from the pre-professionalized college level.4

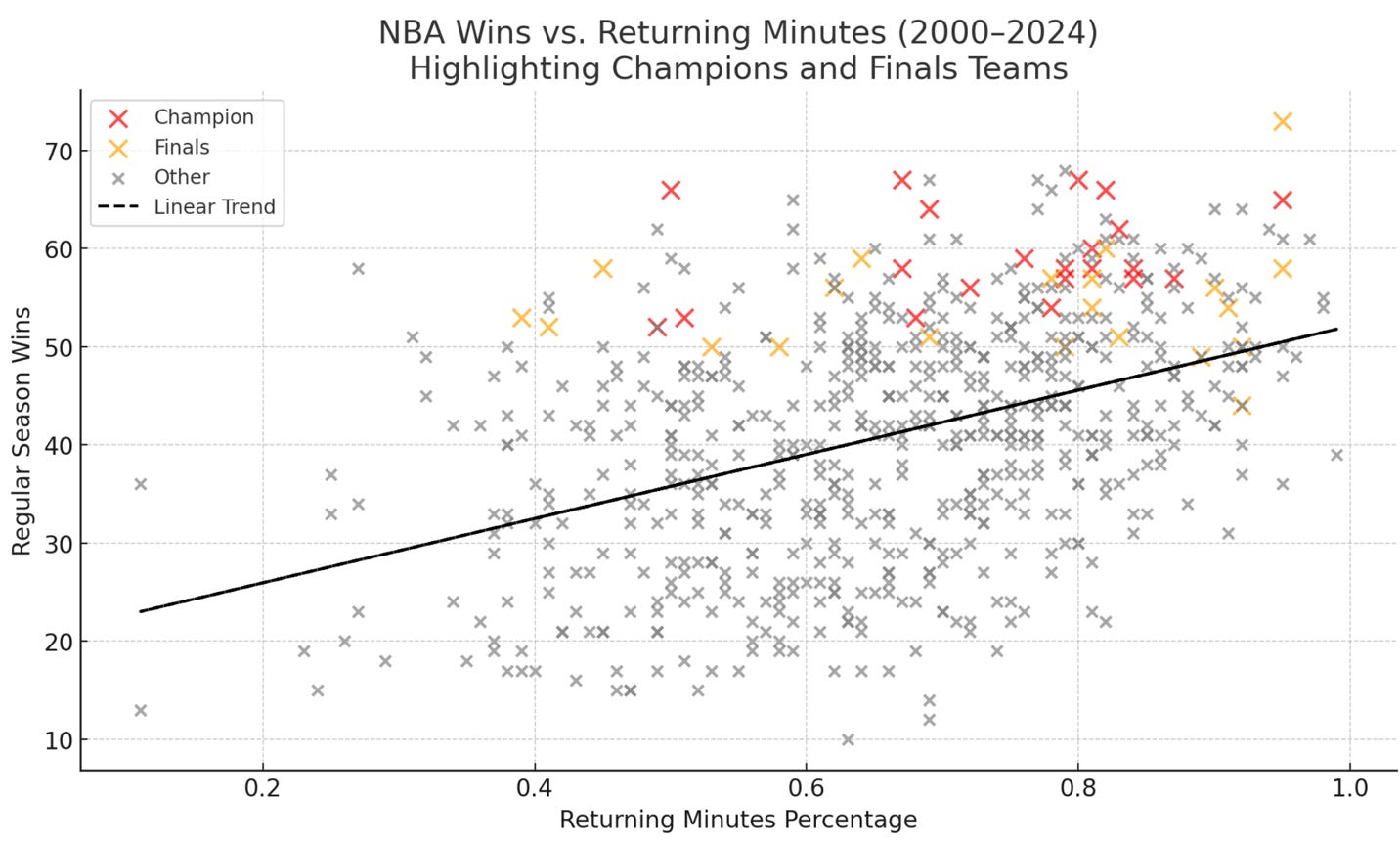

Mapping the 655 different NBA seasons in this dataset shows a noticeable positive correlation between team success and roster continuity, perhaps suggesting that the “win-now” mindset of portal-happy programs is not the end-all be-all strategy.

The data reveals that, with admittedly significant variance (R² = 0.1771), every 10% increase in returning minutes in the NBA results in 3.27 more wins across an 82-game season, approximately a 4% increase in team win percentage.

Regular season success is a great benchmark, but fans, coaches, and administrators are often more concerned with championships at the conference and national levels. Looking once again at the NBA data, we see that it is exceptionally rare to find these pinnacles of success without significant levels of roster continuity.

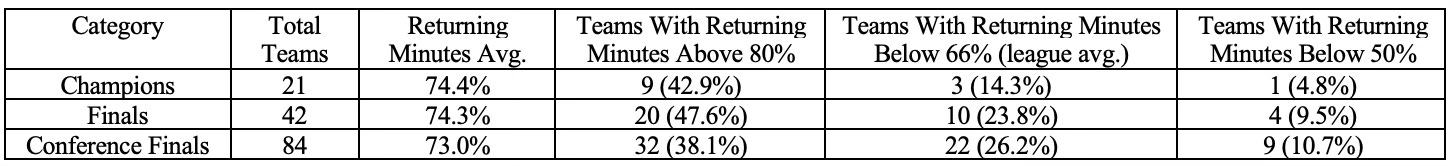

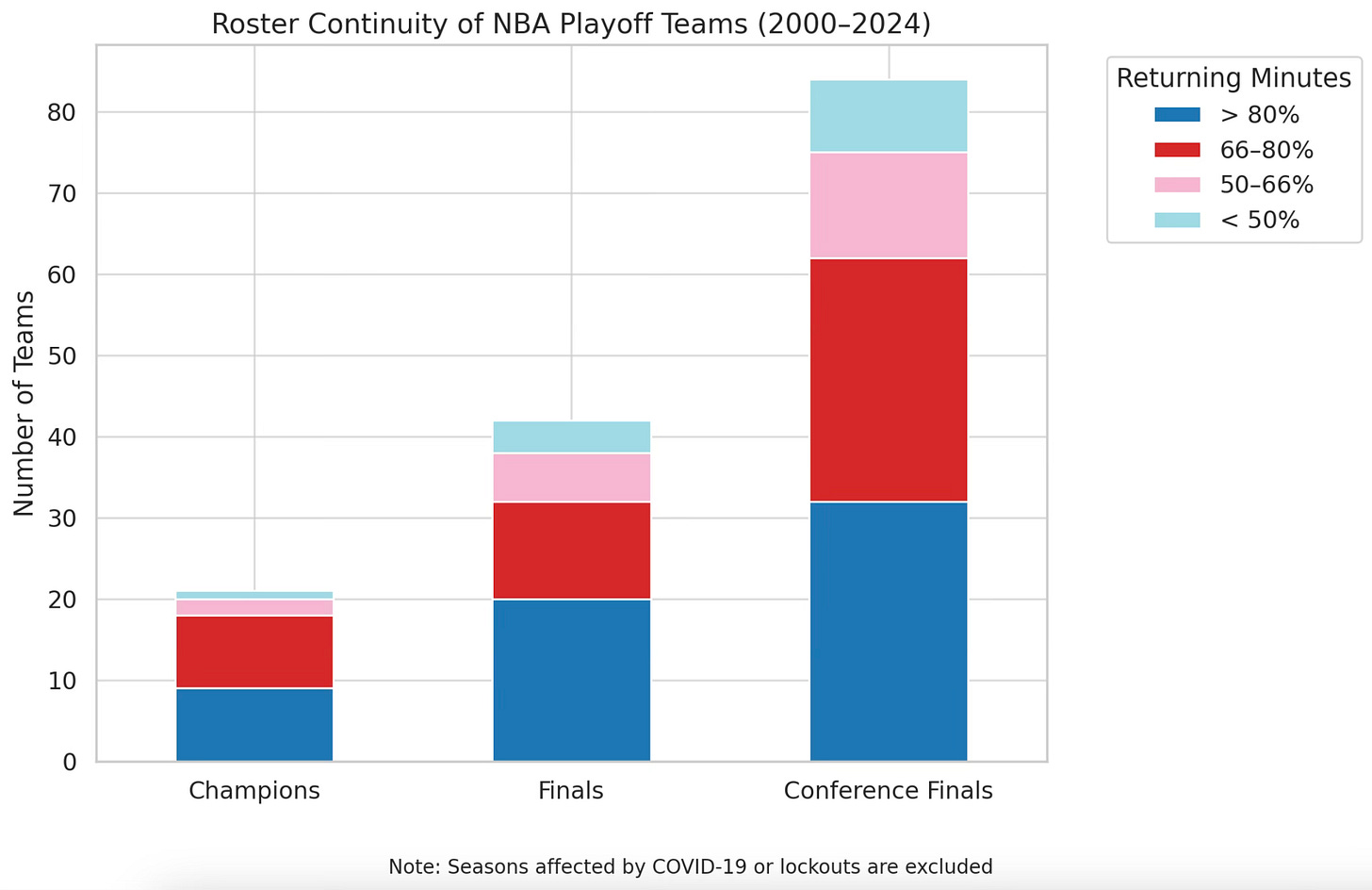

The average return rate of minutes on teams that make the NBA conference finals or better is at 73% (7% above league average). It increases nominally as teams reach higher levels of success.

Only three of the 21 NBA Champions in the data set have had their returning minutes fall below league average — only one champion has dipped below the 50% returning minutes threshold, the 2005-06 Miami Heat, with a 49% returning minutes figure.5

The ability to achieve championship-level success is often found in teams with roughly one standard deviation or more (σ = 15.8) returning minutes than average; teams that return at least 80% of their minutes year to year have won 42.9% of the 21 NBA championships studied and represent 47.6% of teams that made the finals in that period – this comes despite making up only 20.6% of total teams.

When it comes to winning championships (and making the Finals), high continuity teams are overrepresented. Low-continuity teams occasionally make noise, but over three-quarters of teams that make the finals and over 85% of NBA champions have higher than league-average returning minutes. Experience in a system, team chemistry, and, oftentimes, previous postseason experience are key factors that define the importance of roster continuity in deep playoff runs.

So, what does this mean for college basketball coaches and newly minted general managers? Well, there are a couple of ways to look at the data. First and foremost, continuity matters. Athlete retention and the chemistry that stems from its presence at the highest level of professional basketball prove this. At the college level, where zone defense and offensive systems that heavily rely on set plays are more common, the need for chemistry cannot be understated.

Unfortunately, the calculus isn’t that simple. As mentioned earlier, the variance in athletic talent at the college level is much greater than in the NBA. When the margins between the best and worst players on the court are razor thin, variables like continuity should have a greater impact. The impact of continuity on wins at the NBA level is likely higher than in college because the skill gap at the highest level is so close between individual athletes.

With limited funds, college basketball teams would be unwise to think continuity is a sure-fire path towards success. That said, the ever-increasing ability of teams to implement multi-year deals through revenue-sharing agreements allows for creative solutions to bolster retention without breaking the bank.

Schools at both the high-major and mid-major level may prioritize spending more upfront on recruits to secure athletes for longer.

One emerging concept is the introduction of a "right of first refusal" (ROFR) clause into multi-year revenue-sharing agreements. Acting like the NBA’s restricted free agency system, this would give schools the contractual right to match any competing NIL or revenue-sharing offer an athlete receives during or after the term of their deal.

While athletes would retain freedom of movement, ROFRs provide schools with a legal mechanism to retain talent they’ve developed, without being forced into bidding wars or overpaying up front.

In the NBA, front offices have long leveraged multi-year deals, team options, and restricted free agency to manage talent costs and maximize roster value. Rising players often accept long-term security in exchange for slightly below-market deals.

Increased spending upfront on multi-year deals, including team options, allows programs to minimize the risk of long-term, inefficient expenditures towards athletes who don’t pan out, while providing massive upside for athlete retention on team-friendly deals. This is especially important for smaller schools, which are often burned by their most successful high-school recruits.

As college basketball programs prepare for revenue sharing and annual basketball budgets become stabilized, borrowing strategies from the NBA and other pro models will become essential. For the best teams, continuity won’t be an accident.

While efforts to curb third-party NIL spending outside of the cap are in place, many schools, through large upfront payments made before the settlement issuance, have skirted these restrictions for the 2025-26 season. While the 2025-26 cap is $20.5 million, the rev-share cap will grow with every subsequent season.

For clarity, 'returning minutes' refers not just to the amount of time played by returning players, but to the percentage of total team minutes from last season that were played by those athletes who are back on the roster this year.

Data sourced from archival BartTorvik preseason data.

For simplicity’s sake, I have omitted the 2011 lockout-shortened season and seasons impacted by COVID-19 from the data set.

The 2005-06 Miami Heat championship team was involved in a massive five-team trade in the preceding offseason, receiving high-usage players James Posey, Jason Williams, and Antoine Walker. They subsequently acquired a veteran, Gary Peyton, to complement their returning core of Dwayne Wade, Udonis Haslem, and Shaquille O’Neal.